Nagaon district, Assam, India – When you leave a health facility after choosing a family planning (FP) method, who do you reach out to later if you have questions? Experience side effects? Miss a pill?

In the southwestern part of Nagaon district in Assam, that person is often Kunjamani Singha.

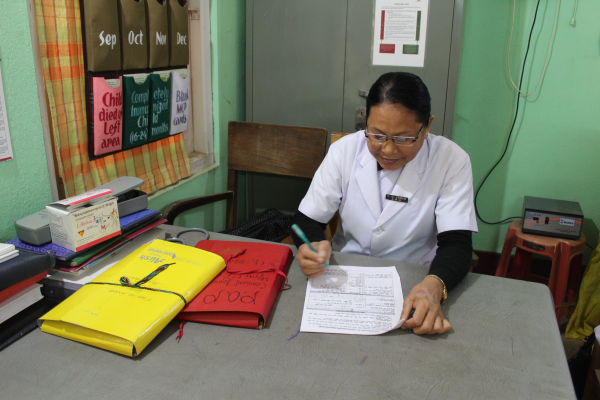

When you first meet Singha, you are reminded of your favorite school teacher. She is gentle, but speaks with authority. She moves swiftly, ensuring the counseling corner at Hojai First Referral Unit (FRU), where she works, is clean and ready before each day begins. With more than 31 years of experience as an auxiliary nurse midwife (ANM) – more than half of which have been spent at the 30-bed health facility –– Singha is known and trusted in her community.

But her responsibilities are broader than being an ANM. Singha is also a FP counselor, a job that absorbs most of her day.

“First I welcome them,” she says of the women and couples who come to her, interested in more information about FP. “I try to be respectful of them and encourage them to speak freely. If I am not mindful of the client, how will they open up?”

After ensuring her clients are comfortable, Singha informs them of all FP methods available. She explains the advantages and limitations of each, as well as how they are taken, their effectiveness, and related, common side effects. Once the clients have voluntary made their choice, she reiterates this information again before screening women for their chosen method.

Singha’s efforts are part of the Government of India’s work to expand the country’s public sector FP options by including newer, proven methods such as the oral contraceptive pills (progestin-only pills [POP] and Centchroman). MCSP supports this work at 52 select public health facilities in five states – Assam, Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, Odisha and Telangana – by working to institutionalize service provision for these newer contraceptives. This includes capacity building of 32,019 community health workers (CHWs) and nearly 300 facility staff like Singha – on the newer contraceptives themselves, as well as developing related information, education and communication materials, job aids, and documentation tools. MCSP also provides supportive supervision visits as this work unfolds.

Assam holds the unfortunate distinction of having the highest maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in India at 237 (versus a national average of 130). While the MMR in the state has improved by an astounding 163 points over the last decade, Assam still has a long way to go to end needless maternal deaths. Critical to this work is increasing access to high-quality FP methods – especially in a state like Assam, which has a record high unmet need for FP of 14.2%.

While her community is increasingly more open to FP, it is still a sensitive topic and many women find it difficult to express their FP desires freely, Singha says. To help combat this, she works to gain the trust of her female clients, encouraging them to talk openly and ensuring their counseling sessions are private. This also includes women in the postpartum ward, who she counsels on FP.

However, Singha’s job does not end once a client accepts an FP method. Because MCSP promotes follow-up with all FP acceptors at prescribed intervals, Singha aims to reach each acceptor by phone at one, three and six months. During these calls, she relies on her MCSP training to reinforce key FP messages, encourage continuation of the chosen method, answer questions, and inquire about side effects. Singha also asks about plans for future pregnancy and, in the case of POP users, counsels women to switchover to a more effective method when exclusive breastfeeding ends.

Ensuring timely follow-up with clients is often a challenging task, she says: “Women leave their mobile numbers with me, but it is very difficult to reach some of them.”

But Singha doesn’t let this stop her. When she is unable to reach clients by phone, she reaches out to CHWs in each client’s village, asking them to do a home visit. She is grateful for their support, knowing their combined teamwork is critical to ensuring client follow-up is completed.

Leisangbi Devi, a CHW who works with Singha to follow-up with acceptors, records her findings from each home visit and reports them back on a weekly basis. This work makes her feel more connected to her community, she says: “I meet [women clients] on a daily basis. That’s why they like me. Otherwise, they would feel that after recommending the [FP] method, I didn’t bother to inquire about their wellbeing and forgot about them.”

The most satisfying part of her job, Singha says, is feeling that her work contributes to a healthier society. This keeps her motivated.

“I like spreading awareness about FP, and mother and child health,” she adds. “I like that I am able to give them knowledge that will help them improve their health.”